|

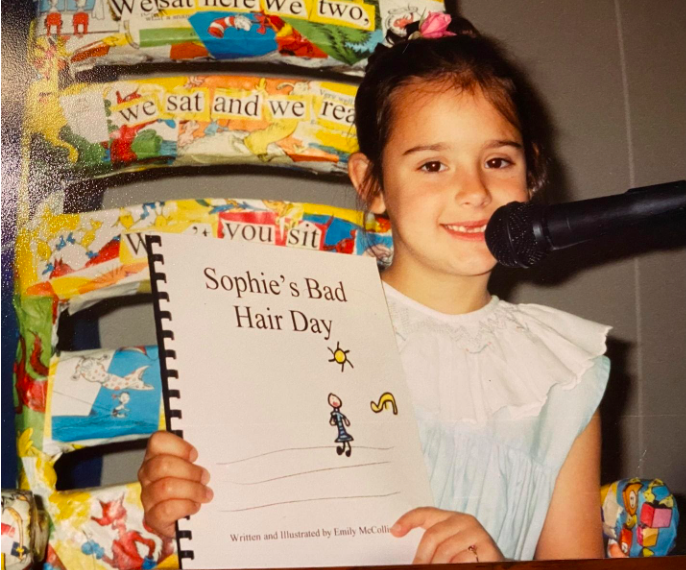

1. When did you start writing? “It is hard for me to pinpoint a time in my life when I wasn’t writing. It feels like it’s been something I’ve always done. I was born, I learned to talk, and I learned to read and write. Beginning when I was small, I was a voracious reader. I was reading many things that weren’t entirely age-appropriate as the youngest of three siblings. I would tuck myself away with a blanket and a book and escape until I heard the call for dinner or my mother’s command to do my homework. Specifically, when I was in the first grade, we all had to write our own little books. We dictated the words to our teacher, who would handwrite the text, and we illustrated them ourselves. When finished, they were laminated and bound by a flimsy plastic spiral. My book was called ‘Sophie’s Bad Hair Day.’ We held our books and read them aloud at ‘Author’s night.’ I suppose that was my official career launch.” Emily in first grade, 2. How did you get into writing poetry? “When I was a 14-year-old, I watched a BBC movie called Bright Star. The movie is about John Keats’ life, and if you know anything about Keats, you know he died young. It was a deeply moving movie, sad and full of poetry. I left the living room where I’d watched the movie, my face still wet with tears, and grabbed a journal. I sat in my bedroom and wrote my first ever poem. It was dramatic and wrenched with 14-year-old heartache. It was about a boy I thought I loved. It was full of declarations and angst, as you can imagine. Although this poem is something I never hope surfaces, it launched me into writing poems as journaling, a practice I’ve never stopped. I think after that, I knew I would be a creative writer of some kind. I thought I would write the next great novel and began college as a Fiction major before quickly realizing that my natural inclinations were different from Fiction writers. I switched to poetry and non-fiction and never looked back.” 3. How did you get into writing non-fiction? “When I was a freshman in college, I was a fiction major at Columbia College Chicago. During my second semester, I already knew I would change my major because something about fiction wasn’t clicking for me—despite my love and passion for creative writing. I took a non-fiction class and learned what creative non-fiction was for the first time. That semester, we wrote a handful of personal essays in class, and I was hooked. What wasn’t clicking in fiction classes clicked in non-fiction. When I transferred from Columbia College Chicago to Louisiana State University (located in the city where I’m from) to finish my undergraduate degree, I decided to major in poetry because there was no non-fiction concentration there at the time. That was an excellent decision for my life. I had always loved poetry and written poems; I just didn’t realize you could do that in college or your career. It was a tremendous awakening that I could be both: a non-fiction writer and a poet.” 4. Where do you draw inspiration? “I certainly draw inspiration from the world around me: the people I love, the places I go, the terrains I witness, something a customer says at the coffee shop, the squirrel that makes aggressive eye contact, or the phone call I have with a friend. I draw inspiration from my own educational journey reacquainting myself with my own culture, language, and heritage as a Cajun-Creole person. I draw inspiration from S. Louisiana, where I was born and raised, where my family has been for generations. I also draw inspiration from my life experiences, positive and negative. My poems often consider creolization, Cajun identity, disconnection from heritage, assimilation, and family. Other times, my poems engage with connection to body, reclamation of self, identity, sexuality, and certainly criticism of religions, specifically Christian Evangelicalism. One of the many reasons I grew up somewhat disconnected from my own cultural identity is Evangelicalism. I also experienced many traumas (end of the world trauma, purity culture trauma, hell trauma, etc.) from my years raised in fundamentalist Christianity—and I was in an Evangelical cult from age 16 to 22. Having survived these experiences, as a survivor of sexual assault and violence, as a queer person who grew up being told they were sinful for existing, and as a person who has reclaimed space to live, I need to continue considering these experiences instead of moving beyond them without reflection or engagement with the systems of power that function to oppress people.” 5. You are currently pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Southern Mississippi. What brought that about? “When I graduated with my undergraduate degree in 2016 with a BA in English—creative writing/poetry, I had no idea what I would do. My immediate plans included helping some friends open a music venue and creative workspace called The Parlor in Baton Rouge. I was the nighttime manager and music booker for the space. I thought I’d spend a few more years in the music scene before finding my next gig. However, there isn’t much money in local music scenes, and I realized I needed other work relatively quickly. During this time, I waited tables, taught poetry to elementary school children, and worked in the grant department of a non-profit. When the music venue closed, I started working in specialty coffee as a barista and barista trainer and did that for a few years. I loved music, and I loved coffee. All the while, I was still writing new poems and going to poetry readings and reading at poetry readings. Around this time, I started reading my work alongside a local experimental musician and performance artist, Hal Lambert, and we’d do our sets together, sometimes to open for music shows. I recorded my poems on a few local albums too. It was a blast! All the while, I was trying to find my thing. I knew poetry was my thing, but I discovered, over these years, that teaching was my thing too. When I realized how much I enjoyed and cared about teaching, it made sense for me to think about an MFA. I applied to a ton of MFA’s, got into a few, and ultimately decided to move with my spouse to Lexington, Kentucky, for UKY’s program. I had an excellent two years of writing, teaching, and learning. While I was completing my MFA, I added a graduate certificate in College Teaching and Learning. I found that I wasn’t only dedicated to teaching, but I really cared about pedagogical theory. I decided to apply to Ph.D.’s to continue to gain additional teaching experience, keep writing, and keep considering pedagogy as a discipline. At the same time, I was considering an entry into the academic job market, a rather hostile market to enter. My husband and I decided to choose USM over other options because it’s only a few hours away from our families in Louisiana, and we enjoy the food and climate of the deep South. I also knew I’d be closer to source material if I wanted to keep writing about Cajun-Creole history and identity.” 6. You’ve started a teaching blog. How is that experience so far? What is your vision for your blog? “I added a teaching blog to my website because I’m passionate about demystifying knowledge. This semester, I’m in a pedagogy class where we must read certain books and articles and post reflections on our teaching every few weeks. Rather than write these reflections on a private blog and read these resources just for class, I decided to make my blog public and share each class reading. I think pedagogy should be a communal conversation, and we should all be encouraging one another to teach better and more equitably. Folks teach at all different age levels in various kinds of institutions. Certainly, there is a difference between K-12 teaching and teaching in higher education, but some of the principles are the same. I also know that not every graduate program provides its students with resources and information about good pedagogy. Yet, they still expect those same students to teach introduction classes (which are formative to college student’s experience). Since I have to do the work anyway, I thought I might as well make the knowledge public! I enjoy reflecting on the readings and my teaching, and I’m determined to be an excellent teacher, which requires self-reflection and a willingness always to improve. Regarding the scope of my teaching blog, I would like to keep posting after this semester ends. I want to write other blog posts that aren’t connected to the class material directly—for example; I’m working on one right now about gendered language and gender expectations in higher education. Overall, the more those of us who teach talk about teaching, share information, and value transparency, the better off we will all be. This kind of transparency is counterintuitive because, in higher education, you usually don’t talk about any faults, failures, or room for improvement. The institution of higher education isn’t conducive to that kind of conversation—this is reinforced by the tenure process where your peers are the ones who decide whether or not you’ll receive tenure.” 7. What do you hope people take away from your work? “I really would love for people to have some connection to my work—whether that be laughing, cringing, gasping, sighing, crying, or ruminating after the fact. There’s not necessarily one thing I want to send people out with. I hope that my transparency and honesty about my intersecting identities and my willingness to be loud about them, and about my recovery from religious trauma, emboldens people to love themselves, to feel confident in their decisions, and to leave abusive spaces like harmful/toxic theologies. If one queer person feels validated, or one person grappling with religious trauma feels affirmed in their identity outside of religion, I would feel immensely satisfied. At the end of the day, I’d love for people to engage with my work, but I write as a process—archiving my own experiences to move beyond trauma towards joy and liberation.” 8. What other project(s) do you hope to take on someday? “I’m currently working on a book of poems, a chapbook of poetry, and a secret project. In the future, I would love to publish academic articles about pedagogy in creative writing, I’d love to write a memoir or book of essays, and I’d love to publish non-fiction about sexuality post-purity culture. A large-scale project I hope to take on one day is examining Cajun-Creole representation in American, Canadian, and Caribbean literature to see if I could compile a comprehensive collection of literature future scholars can reference to discuss the Acadian diaspora. I’d also like to write a non-fiction book about the Acadian diaspora—what happened historically, the attempted ethnic cleansing of our people, and how we ended up in Louisiana. A few books exist that do this, some dryer than others, but collectively, very little literature exists on these topics.” 9. What’s the best writing advice you’ve been told or overheard? Or, what writing advice would you offer? “The best advice I’ve ever received was that you should read more poetry if you want to be a better poet. It’s so simple, but *chef’s kiss* it is spot on advice.” 10. And finally, what do you enjoy doing that you don’t talk about enough. Tell me all about it! “I absolutely love reading romance novels (especially fantasy or paranormal novels). Growing up the way I did, sex was taboo, and even thinking about sex was sinning. I was discouraged from reading/watching any content that even had sex implied! As an adult who has reclaimed their body and embraced a personal sexual ethics who now supports consensual sex in any form, I had no problems with romance novels, but I just didn’t read any for a long time. I think, as writers, especially in academia, we’re told that specific genres are more valid or ‘more serious’ than others. That’s obviously super problematic, but it does make its way into your subconsciousness. This past year, I finished my MFA in a global pandemic and realized I wasn’t reading for fun anymore. I started reading fantasy again and, through suggested books, read my first fantasy romance novel. I loved it! Since December of last year, I’ve read 400 books. The last time I read books like this, excitedly and late into the night, was in high school. I feel like I rediscovered the fun of reading books, which eliminated some of the cynicism I may have been harboring toward a career in writing. Essentially, I remembered why we do what we do: why we write and share our writing with others.” Hear Emily read their poem "Queer Poem." Emily M. Goldsmith (she/they) is a queer Cajun poet originally from Baton Rouge, Louisiana who attends the University of Southern Mississippi as a Ph.D. student in Creative Writing. Previously, they received their MFA in Poetry from the University of Kentucky. Emily is currently one of the managing editors of Giving Room Mag. Their work can be found in Fine Print Press, Witch Craft Mag, Entropy Mag, Vagabond City Lit, elsewhere and forthcoming in Pile Press.

1. Why did you start writing? "I believe I’ve been writing for as long as I can remember. I started off fairly young with nonsensical fiction stories and exaggerated creative nonfiction before I even knew the distinction between literary genres—I then dabbled around quite a bit with creative essays in middle school, before eventually stumbling upon contemporary poets. From then on, I’ve leaned heavily into studying and writing poetry, because I never quite knew how to exist without it." 2. What is your method of writing? Notebooks, computer? "I most definitely write a vast majority of my pieces on my computer. Notebooks are for workshop drafts or when I want to attempt a piece that’s more complex in its form, and want to experiment with how its shape is or visually play around with it. However, I type far, far faster than I write, and I’m often frustrated if my hands are unable to put down words at the rate I’m forming them in my head. Computer documents are also much easier to send out for peer editing, as opposed to a .jpeg file of my hurried (and often a tad worrying) handwriting." 3. Where do you draw inspiration? "Upon attending a workshop lecture with Kevin Wilson, where he spoke about his novel Tunneling to the Center of the Earth, I had the honor of hearing him talk about his inclination for including oddities and strangeness in his work: the act of putting the bizarre or the ‘weird’ down on a page could be a way to reconcile your loneliness in such a vast world. Lately, I’ve been drawing my inspiration from this, in a sort of way: I want to write about the strange, the things unspeakable to me, so that I know there are words out there grappling with my same existence, too, and the small little ‘nicks’ in my mundane. But I also wish to write about the beauty of these things: the sublimeness that isn’t overshadowed by the peculiar. Overall, I suppose I find myself diving into the range of the human experience of how we live with ourselves and the terrifying things that surround us—like grief, hurt, and love." 4. How do you know when a poem is done? "When the poem stops being something I can ‘juice,’ in my words. I often write a bit narratively, and when a conclusion comes, it’s when I feel that the poem has nothing left to say to its audience." 5. How do you title poems? "My Adroit Journal mentor, the brilliant Gabriella R. Tallmadge, was the one to push me to be more deliberate with my titles! The fact that the title is the first line of a poem, and that there is a large, large difference between a good title, and a stellar title—all things Gabriella hoped I would learn and practice. With her advice, I title poems so that it always adds something beyond what the poem already says. What new lens does the title give? Does it help contextualize in a purposeful way? Does it drive home the unsaid? I’m a title nitpick, now, thanks to Gabriella’s guidance." 6. You are the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Interstellar Literary Review. Why did you decide to establish your own magazine? "To be quite honest, in Interstellar’s very short initial period of being founded, I was unaware that the literary magazine scene was so broad! I had discovered a handful of magazines that I adored for helping to give writers gorgeous, meticulously crafted platforms, and so I genuinely and naïvely thought I was adding to a small scene of helping purvey the literary arts by founding my own magazine. I soon discovered that the world of literary journals was far, far larger and more established than previously thought, and I’d unknowingly (but all the happier for it! Interstellar is a beloved child of mine, and I’m forever grateful for my contributors, staff, and the community that’s helped us thus far!) dove headfirst into it." 7. What other project(s) do you hope to take on someday? "Ambitiously, I hope to dabble with somehow combining my writing and visual art in some sort of way—perhaps film, because I’ve always found it fascinating and immensely full of potential! I’m also considerably ardent about promoting a love for poetry beyond its current sphere, as well as just general community involvement and guidance in poetry, so hosting workshops isn’t too far away an idea that would come from me. (And also, a chapbook of my own in the distant future … but you didn’t hear that one from me! It can be our secret.)" 8. What do you hope people take away from your work? "I don’t want to be so bold as to say that my work is life changing. My most sincere hope, though, is that something in any of my poems can resonate with someone, regardless of whether it’s exactly what I wished to say or not. I just want so very, very, very much that someone can feel that their small existence is not quite so untouchable, after all; there is someone out there that exists that was, at some point in time, as inescapably human as you feel right now—and here my poem is as proof of it." 9. What writing advice do you find totally useless? "It’s hard for me to knock on any writing advice, just because I feel that so many things work or don’t work for different people based entirely on their preferences. Personally, though, the advice of cutting out strips of lines from a work and rearranging it has never quite done it for me. Like I mentioned before, my pieces often involve narratives of sorts, or some form of a linear progression, so ‘remixing’ tends to mess up my flow." 10. And finally, what do you enjoy doing that you don’t talk about enough. Tell me all about it! "I truly do not talk enough about how much of a jock I am. I’m currently a captain of my soccer team, and I’ve been itching for a bit to somehow dedicate something literary-related to this, but alas! To no avail. Also, fashion, capturing moments with friends, making a proof of love permanent in the face of time—sentimental little things, I wholeheartedly and unashamedly adore doing. I also thoroughly enjoy calculus, because I am a freak sometimes, and would love to mentor people in it! Mentoring in general is very enjoyable for me, but mentoring math especially feels very comfortable." Hear Sunny read her poem "Poem In All The Wrong Ways." Sunny Vuong is the founder and editor-in-chief of Interstellar Literary Review, and an alum of the 2021 Adroit Journal Summer Mentorship program. Her work is featured or forthcoming in Diode, Strange Horizons, and Kissing Dynamite, among others. Connect with her on Twitter @sunnyvwrites.

1. When did you start writing? "I wrote a lot of poetry in High School (mostly bad) and college (a little better) and then abruptly stopped as I went to grad school and became a teacher and a father. Every so often I’d teach a poetry unit and I would write something (still not that great). A couple years ago, my grandmother passed away. In the months leading up to her passing, she would ask why I wasn’t writing. She had a binder full of my poems and stories from the past 25 years printed out from emails and tucked away. When COVID hit and lock-down started here in NYC, I thought of that and said to myself ‘What are you waiting for?’ I started trying to write in earnest that April and here we are. Now I write or think about writing every day and have incorporated it into my routines and lesson plans and the way I approach daily life." 2. Where do you draw inspiration? "My daughters are five and ten years old and they both say and do things that shock me, because they never follow the habits or logic that I’m expecting as an adult. Sometimes that is distilled right into a poem; other times it is just useful to think about how to break from my much more boring mind. When I’m not thinking about them, I am focused on my grief, still life paintings, or nature and nature documentaries (especially David Attenborough). I am an avid reader and often read in obsessive bursts, like only poetry or only nonfiction about climate change or all of Toni Morrison. My writing tends to work in the same way. I will latch on to something, a phrase from a poet, a topic from the last poem I wrote and then try to write around that. My process is still evolving and I’ve learned to trust it and just ride things out." 3. What is your method of writing? Notebooks, computer? I type almost all of my poems on a single gdoc file called 'Textual Mess.' It is a scrap heap of lines or titles or ideas or prompts I’ve given myself. Some of them sit there for months. The document is a workshop space. When I finish a poem draft, I will paste it into another file titled something like Poems July – September 2021 but I’ll often grab from those, paste back into the textual mess and tinker or cannibalize a poem in service of another. Sometimes, if I’m in a drought, I will go back to using a little notebook and try writing some lines in there, but I will switch back to my computer if the poem starts getting momentum. 4. Could you share your process and thoughts on writing? "I used to think that writing was every day at a set time and I know a lot of writers who do this for various reasons, but as with teaching and parenting, I need to go through low periods or let things simmer so I am learning to think and tinker and write without the pressure of a finished draft until the rhythm returns and so far it has. I was writing one poem a week for a couple months and then a chapbook MS cohered in the space of two weeks. Writing is also not a solitary thing. I send work to my writer friends for feedback and they help punch holes in the work or find out where the music of a line resides. When they write back ‘Holy shit, Jared’ I know that I’ve got something. Having friends who send me their poems or manuscripts to read, who share their successes and acceptances, helps me think about the structure of things I’m working on or share the glow of what they are feeling." 5. How do you know when a poem is done? "I will get to a point where the poem doesn’t seem to want to go any further or I will have developed a punch for the end (think of the heroic couplets in traditional sonnets). If I have a through-line to that end that isn’t just a load of imagery then I know I have a draft to start putting final touches on. However, there are times now when I will go back and look at a poem I’ve published and start paring it down or cutting a stanza because my style has evolved. So I guess ‘done’ is relative to the time and headspace I’m in." 6. What can you tell me about your works-in-progress? "I have a short full-length manuscript (54 poems) I am working on and molding to cohere. It is most of my stronger, published poems set in clear sections, so I’m in the process of building a larger through-line for the work as a whole. I also have a new chapbook MS about climate change that I feel good about and have been shopping around. I vacillate between thinking this is part of the larger manuscript or the beginning of something else that could be larger." 7. What other project(s) do you hope to take on? "I wrote a poem called ‘The Challah Uprising’ that was published in the Rise Up Review that relies on multiple voices, like competing characters or oral histories. If you have ever been to the Holocaust museum, there are rooms of voices speaking their stories from that time. The poem I wrote had very clear characters in my mind and the hint of a larger story of failed resistance and larger tragedy so eventually, I want to explore writing that out into a coherent arc of poems or a polyphonic novel." 8. What do you hope people take away from your work? "I care a lot about how we connect or yearn to connect to a number of things: what we see in art, how we love, what we haven’t said, what we miss as we think from the human perspective about the larger world. I hope that people read my poems and begin to reflect on these strands of (dis)connection for themselves and their experiences." 9. What writing advice do you find totally useless? "I find a lot of writing advice to be useful even if it doesn’t apply to me. Why are they suggesting this, what does it do for them? How does this translate to me. It sounds like a cop-out but I haven’t found anything completely useless, just not as useful to me. As I said earlier, I don’t believe writing is a robotic routine or that you MUST do it every day. I guess I am trying to say that “writing” here means something much broader: walking, observing, joy. The words or ideas will arrive if you are open to receive them—my daughter eating animal crackers out of a large plastic bear led to a prose poem about endangered animals and deforestation, looking at lichen and tromping along a trail led to a poem 2 months later about my daughter growing up. What I am trying to avoid most of the time is forcing a poem to happen or forcing myself to write something good. If I find I am copying my successful work without an idea of what I want a poem to say, I make myself stop for a bit. If I am relying solely on observations and imagery, then I work not to kid myself that I have a poem. So far this is working for me." 10. And finally, what do you enjoy doing that you don’t talk about enough. Tell me all about it! "I don’t talk about my teaching enough. I haven’t written about it as a subject of my poems. It feels too personal in a way and there are probably institutional guidelines that I’ve internalized, like how you aren’t supposed to post about your students online, etc. I have been teaching English Language Arts and AP English Literature for 15 years in the NYC public school system and I taught in some form or another at the college level as an adjunct or TA during grad school. A lot of my time and creativity has gone into being an accessible teacher. When I first started teaching in public school I was coming out of academia into a 7th grade classroom. I had to learn how to translate myself in a way that was clear and also elevated my students without falling into the trap of thinking my knowledge or process for learning was the only template. Now, as I help my daughters navigate their own learning and special needs has forced me to reorient what learning is for and what the ‘success narrative’ means for them and my students at school. This has led to a pretty wonky set of discussions with my colleagues about equity and grading and mastery, which I will spare you the details of here." Hear Jared read his poem "A Florida man ‘thumbed’ an alligator in the eye to rescue his dog from a ‘death roll’ (Or this is how we say 'I love you')." Jared Beloff is a teacher and poet who lives in Queens, NY with his wife and two daughters. You can find his work in Contrary Magazine, Rise Up Review, Barren Magazine, The Shore and elsewhere. He is currently a peer reviewer for Whale Road Review. You can find him online at www.jaredbeloff.com. Follow him on twitter @read_instead.

1. When did you start writing? "I would say that writing has always been part of my life. Even before I knew how to read and write, I enjoyed telling people around me about the fictional worlds and characters I would create. However, I'm assuming this is talking more about the idea of having this big break in which I started taking writing seriously. In that case, I participated in NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) in the 8th grade. I had the grandiose idea that I would be able to write a novel in a month. Needless to say, I did not quite achieve that goal. Yet the fast pacing and intensive focus on writing made me realize that I enjoyed writing beyond the classroom. But don’t mistake me for ‘an OG teen writer’ — I learned what a lit mag was in 2020! Though I’ve officially ‘started writing’ quite a while ago, I’m still constantly experiencing new beginnings in my writing journey." 2. What is your method of writing? Notebooks, computer? "Google Docs, Google Docs, Google Docs! Even though I like the aesthetic and idea behind writing in a leather bound notebook or on a vintage typewriter, I shamelessly choose function over form. I find that using Google Docs allows me to copy and paste lines around and enjoy the speed and efficiency that comes with using a keyboard. However, I keep notebooks in my proximity whenever possible since I also like to (very messily) jot down incomplete lines and basic ideas when I’m away from a screen." 3. Where do you draw inspiration? "When I started writing, I had believed that I needed to write only about the extraordinary and unusual. Now, I think that's far from the truth. My current philosophy is that it's more important to write extraordinary lines rather than write about extraordinary things. Therefore, I'm not afraid to find inspiration in mundane places. (For example, I find great enjoyment putting new spins on everything from kitchen utensils to supermarket trips.) Another inspiration of mine is pop culture, though I aim to use pop culture as a tool rather than the overwhelming message behind the entire piece — my hope is that people who haven’t seen/experienced the media I’m talking about can still access my work about it.." 4. Could you share your process and thoughts on writing? "My process is very nonlinear and I’d even call it chaotic at times. I don’t have a set schedule for writing, but I often find myself in front of a blank page and creating new lines regardless. I really like being able to see progress between the different renditions between each piece so I often copy-and-paste the same poem many times in a Google Doc while I edit and edit again." 5. How do you know when a poem is done? "Short Answer: I don’t. I would say that my poems or more so stopped as opposed to complete. I find that there are always going to be lines I can edit or concepts I can improve. Nevertheless, I accept that I am very human and subsequently imperfect. If I can read through my work and have the small feeling of ‘hey I wrote this?’ or ‘this was clever of me’, I call it a job well done." 6. How did Preparing Dinosaurs for Mass Extinction come about? When did you realize you had material for a poetry book? "I wrote the titular poem first. And then I wrote two more poems specifically about dinosaurs. At that point, I thought I was on the way to creating some type of narrative. With that, I decided to revisit the medium of a chapbook. I previously attempted to create chapbooks for the sole sake of creating chapbooks which didn't work out well. But with this body of work, the progression from a handful of poems to a poetry collection was much more natural — as if the work itself demanded to become a narrative larger than itself. Most of the poems were actually written in an order similar to that of which they're presented in the final draft. The poems seemingly tied into one another so tightly that I didn’t feel like they would make nearly as much sense as standalones. Eventually, Preparing Dinosaurs for Mass Extinction existed with its own set of recurring characters, distinct images, and narrative structure." 7. What do you hope people take away from your work? "I think the scary thing about having the chapbook out in the world is the fact that I no longer have full control over how it’s seen. In a sense, I am no longer the subject of focus when my work is being read — my words are. Friends, family, and even editors often read my work with me as a person in mind. However, that’s usually not the case with an audience. In a sense, I don’t think I get to control the lines or motifs that resonate with people. However, I just hope that people take away something whatever that may be. I hope that even when people are unfamiliar with all the context and backstory involved with Preparing Dinosaurs for Mass Extinction, that they’ll still find some solace and understanding in my exploration of our momentary nature. Likewise, I hope the same for all my previous work and all my work to come." 8. What project(s) do you hope to take on? "I sometimes code. Earlier this year, I found that it was possible to combine an enjoyment for coding with my writing. I've created a few multimedia and experimental works using a few simple lines of code. I find this idea to be the potential start of many more new poems to come." 9. What writing advice do you find totally useless? "‘You should write in silence and reflection.’ I think this approach works for a lot of people, but I personally did not resonate with it. I’m naturally an energetic person who finds inspiration in the loudness of life. Additionally, I find that discussion (in the form of workshops and peer editing) has been just as important as reflection for my writing process. I feel that it’s almost a stereotype for poets to be the silently reflective type (and it is a very valid process some genuinely prefer), but I don’t think it should be a rule." 10. And finally, what do you enjoy doing that you don’t talk about enough. Tell me all about it! "I’d say I really enjoy mentoring or just sharing my experience in general. I’m very, very far from reaching the Secrets of the Universe™, but I still find it valuable to give back to the communities I’ve been involved in. Both within the world of writing and outside of it, I find that I have a lot of gratitude towards people who have shared their wisdom without expecting much in return. And I’m pretty sure that the world can always use a few more people like that." Hear Rena read her poem "To T-Rex, the King." Rena Su is a writer from Vancouver(ish) and writes a little too frequently about dinosaurs, cyborgs, and offbeat pop culture references. Her work has been recognized by the Pulitzer Centre, The Poetry Society of UK, the Alliance for Young Artists & Writers, among others. When not writing, Rena enjoys coding impractical things, watching documentaries, and playing the ukulele. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter @RenaSuWrites.

1. Why did you start writing? "I’m not sure to be honest—this is a tough question! I never had any serious ambitions to become a writer when I was growing up. I did write during my early teenage years, but it was throw-away fanfiction that I kept to myself. I definitely liked writing, but I wouldn’t call myself a writer then. I wouldn’t even call it a hobby at that point. I guess toward the end of high school is when I got interested in poetry, and then it was very much a teenager-y, vent-y kind of impulse. I didn’t know anything about poetry—I wasn’t even aware that there were still poets around, as wild as that sounds! It was mostly just lineated rants. I can be hesitant to share my emotions, so I wanted to have a place to put my angst so I didn’t take it out on others. I think that still rings true (at least partially) for why I write." 2. What is your method of writing? Notebooks, computer? "I almost exclusively write on my laptop nowadays. I used to be very much into the whole longhand thing—I’d fill a journal every couple of months with poems—but I have some health issues that affect my ability to write like that now. I think my brain works better when I’m typing too. I can get the thoughts out before I have a chance to pre-edit them, whereas with pen and paper, it’s so slow going that I don’t really feel like I’m getting the truest expression of my thoughts. I do use the notes app on my phone if I have a thought in the middle of the night, but I never finish poems on the phone. It never feels right!" 3. Where do you draw inspiration? "From anything I can get my greedy little hands on. My brain needs to constantly be engaged, so I absorb a lot of content in my day-to-day, whether I’m reading, watching TV, writing, listening to music, playing video games… the list goes on! My series of Sue poems is inspired by the character of the same name from Fire Emblem: The Binding Blade. I used to do a lot of Greek Myth persona work, inspired by Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Analicia Sotelo, and Madeline Miller. My more poem-y poems (for lack of a better explanation) are often inspired by music or other poems—especially the work of Melissa Ginsburg, Jennifer Chang, and Suji Kwock Kim." 4. How do you know when a poem is done? "I really don’t. I tell my students all the time that—regardless of genre—a piece of writing is never truly done, but you just have to get to a place of satisfied enough. I could read work I was proud of a year ago that I felt like was done then and have a million edits and revisions in mind. I’ve ripped poems apart in revision that I was proud of at the time of writing. It’s a never-ending cycle to me. Some people might find that intimidating, but I find it comforting—that the poem can grow and change and move through life along with me, and maybe someday, I’ll unlock the secret it wanted to tell me all along. I feel so ungrounded when I talk about poetry this way, but I really believe it!" 5. You are currently pursuing an MFA at Northern Michigan University. What brought that about? "I guess I didn’t know what else to do! It felt like a logical progression for me. I didn’t feel ready to enter the job market after graduation, and I didn’t feel like my poetry was ready for bigger projects and submissions. I don’t know why I thought applying to MFAs was going to be easier—I just thought I had nothing to lose! I really love the classroom workshop, too. I think the most valuable part of my process is talking through my work with others, seeing what others are doing. I find I learn the most when I need to critically examine the work of people right in front of me and see their composing and revision processes. It’s certainly not necessary to get an MFA to be a successful writer, but for the way my brain works, it felt like an organic progression. MFA programs in general are a difficult nut to crack though, so if you’re reading this and are interested in applying, just be aware of what you’re getting yourself into. So many of them are very racist, sexist, and queerphobic, and NMU is no exception. NMU as an institution is rife with issues—faculty are working without contracts, graduate students are paid a starvation wage, and the administration is full of people who certainly don’t have our best interests at heart—and I’m affected by these issues in very direct ways. Still, I’m grateful for the community of writers at NMU. They’re some of my greatest friends, and despite the institutional issues, I’ve never felt more confident in my work." 6. You are the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Von Aegir Literary, a brand new poetry journal. Congrats! Why did you decide to establish your own magazine? "Over the past year, I’ve been an associate poetry editor at Passages North, NMU’s literary publication. I found a lot of satisfaction in that work. I love the act of reading and responding to poetry, so it felt inevitable that I would eventually open a mag of my own. I’m a huge fan of Fire Emblem—I’ve been playing since I was 11 or 12—so I really wanted to carve out a niche for poetry about and responding to the franchise. I’ve done a lot of work revolving around Sue, a background character from Fire Emblem: The Binding Blade, and I wanted to see how other people resonated with characters from the franchise. It’s been an amazing experience to see how enthusiastic people are about this, and I really appreciate it! Even after only a couple weeks, I feel like Von Aegir is already a success, if only for what I’ve learned in the process." 7. What do you hope people take away from your work? "I have no idea! I’m just a dude. That’s a really cop-out kind of answer, and I’d like to think of a better one, but I really can’t. I just try to be honest about how I see the world and how my memory works, and I hope people take something away from it. Even if they hate it or are annoyed by it, I think my work portrays my reality, how I experience the intersection between physical and mental illness. Memory comes to me in shattered images. While I have the training and knowledge to make beautiful images—that’s really present in the work I was doing in undergrad—I find it much more fulfilling to craft a sincere representation of my mind. There’s a chair. There’s a tomato and a knife. Whether or not the tomato means anything to anyone isn’t as important to me as the simple fact that these objects exist in the same space. I think there’s beauty there. I just want to make poems that exist, and hopefully that work resonates with others!" 8. What other project(s) do you hope to take on some day? "I haven’t been able to pull together a chapbook or full-length that I’m proud of yet, so I think that’s my next big hurdle. I’m a pretty unreliable poet! I can’t be trusted to write about one theme or character consistently, so crafting a collection is a pretty dauting task. I move from Sue to more personal work to pastoral poems to fanfiction… etc. I’d really like to have a book, and I believe I will someday! I just need to buckle down and think about what I want out of these poems, what story is most pressing to me. Obviously I’ll need to figure it out, as I have a whole creative thesis looming on the not-so-distant horizon! I’d like to complete a musical project someday, too, if I can ever force myself to try to write songs! I can play guitar well enough, and I can write poems well enough, but the intersection between those things eludes me. There’s some kind of muscle that governs the alchemy of these things (probably something to do with melody) that I just can’t quite grasp. Again, I believe I will someday! I just need some time to focus on something new, and between writing and teaching and learning, I don’t have a lot of time to devote to music." 9. What writing advice do you find totally useless? "Writing every day, reading every day. I’m only human! It’s hard for me to force myself to write when I feel like I’m not feeling. Like, if I’m not ready to give the material up, if I feel like I need more time to figure out exactly how I feel about the material, whatever comes out of me is going to be underwhelming. I don’t handle that outcome well. I have to wait until I’m comfortable and settled with a feeling before I can make myself write a poem. This isn’t to say I don’t believe in inspiration—I think I’m almost always inspired—I just don’t really know what to do with it. Ultimately, I think I’m a poet when I need to be a poet, even if that’s only once a month. With reading, it can just get so exhausting, especially if I’m reading poetry. My brain tends to get caught up in the craft aspects—lineation, caesura, enjambment, etc—so it almost always feels like an assignment. It takes a lot out of me to read a poem, so I’m pretty slow in my work. My brain just can’t take it. I’m much better at reading novels, and I think it’s because I have such limited formal education about their craft. I’m not trying to figure out how to write a novel while I’m reading. I’m just enjoying the story!" 10. And finally, what do you enjoy doing that you don’t talk about enough. Tell me about it! "I’m tempted to talk about fanfiction here, which is really embarrassing—yikes! But that’s how I cut my teeth, so I feel like I need to honor that in some way. I wouldn’t be a writer without it! I have two WIPs right now, both currently sitting at about 30,000 words, and I’m vaguely planning what I’d like to do for NaNoWriMo this year. Since I spend so much time encountering writing in formal academic settings, it’s such a relief to be able to step away from that and write about my favorite video game characters instead! Unfortunately, I think I’m a pretty boring person otherwise! Pretty much all of my hobbies point back to my creative work. Even sleeping, which is my favorite thing to do, produces dreams, which sometimes become poems! In general, I’m an active dreamer, and I love dreaming. Lots of my dreams are—as dreams tend to be—incomprehensible and meaningless, but there’s almost always this unsettling undercurrent to it all. It’s hard to explain, and it’s even harder to explain why I enjoy it so much. I love the logic and movement and entropy of dreams, even if I also find it all deeply disturbing." Hear Heath read his poem "ORIGINS." Heath Joseph Wooten (he/him) is an MFA candidate at Northern Michigan University, where he is an Associate Poetry Editor at Passages North. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Von Aegir Literary, and he has played every Fire Emblem game at least five times. You can find his work in or forthcoming from perhappened, Lammergier, Eunoia Review, and others. You can tell him he's pretty on Twitter @edgy2003blond.

|

writersAmy Cipolla Barnes

Cristina A. Bejan Jared Beloff Taylor Byas Elizabeth M Castillo Sara Siddiqui Chansarkar Rachael Crosbie Charlie D’Aniello Shiksha Dheda Kate Doughty Maggie Finch Naoise Gale Emily M. Goldsmith Lukas Ray Hall Amorak Huey Shyla Jones B. Tyler Lee June Lin June Lin (mini) Laura Ma Aura Martin Calia Jane Mayfield Beth Mulcahy Nick Olson Ottavia Paluch Pascale Maria S. Picone nat raum Angel Rosen A.R.Salandy Carson Sandell Preston Smith Rena Su Magi Sumpter Nicole Tallman Jaiden Thompson Meily Tran Charlie D’Aniello Trigueros Kaleb Tutt Sunny Vuong Nova Wang Heath Joseph Wooten Archives

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed